Puppies and members of the royal court look on as the serious Duchess Anna and Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria face each other across a chessboard. We can only speculate as to why such a modest scene was chosen as a prelude to an album recording, in stark contrast, the ostentatious display of wealth from their marriage and position in society.

Perhaps they wished to stress that, in spite of the precious stones and extravagant jewellery in their possession, their lives were driven more by intellectual pursuits than by the mere trappings of office?

But when we look closely, the attendants aren't even watching the game, are they? Well, one is at least, the chap on the left, and perhaps another; the rest of them appear to have their eyes (and thoughts?) diverted from the issue presently before the crown. Is there an inference here about a lack of trust or treacherous shenanigans afoot? I have no idea. What say you Wikipedia?

"Albert was educated at Ingolstadt under good Catholic teachers. In 1547 he married Anna von Habsburg, a daughter of Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor and Anna of Bohemia and Hungary (1503–1547), daughter of King Ladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary and his wife Anne de Foix, the union was designed to end the political rivalry between Austria and Bavaria.

Albert was now free to devote himself to the task of establishing Catholic conformity in his dominions. A strict Catholic by upbringing, Albert was a leader of the German Counter-Reformation. Incapable by nature of passionate adherence to any religious principle, and given rather to a life of idleness and pleasure, he pursued the work of repression because he was convinced that the cause of Catholicism was inseparably connected with the fortunes of the house of Wittelsbach. He took little direct share in the affairs of government, nevertheless, and easily lent himself to the plans of his advisers, among whom during the early part of his reign were two sincere Catholics, Georg Stockhammer and Wiguleus Hundt. The latter took an important part in the events leading up to the treaty of Passau (1552) and the peace of Augsburg (1555)."

As tempting as it may be to finesse these 'facts' to account for the chess game scene, I'll resist. It was just as likely an editorial choice on the part of the artist, Hans Mielich, who simply cranked out a dutifully solemn scene on a whim, without any specific subtext in mind.

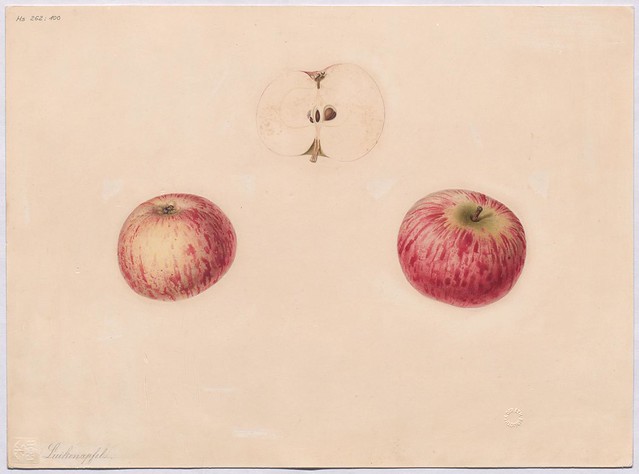

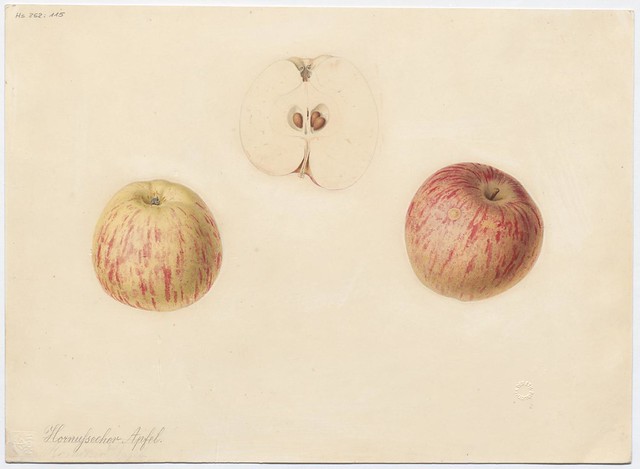

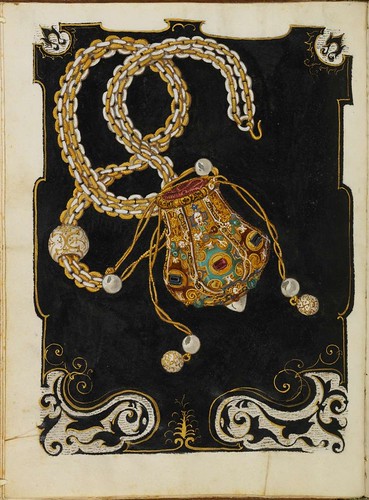

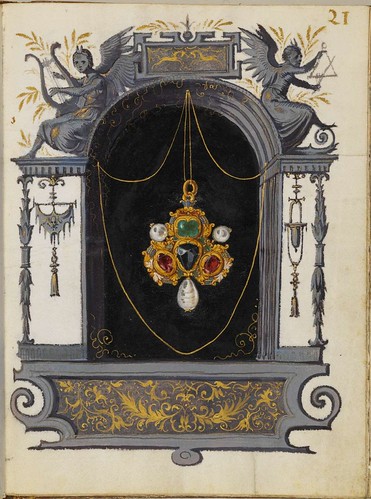

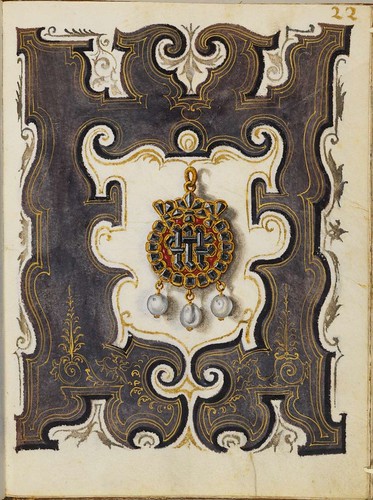

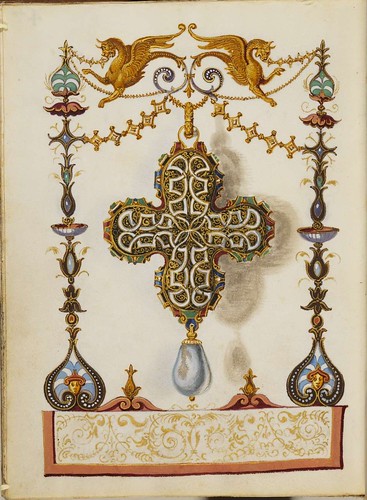

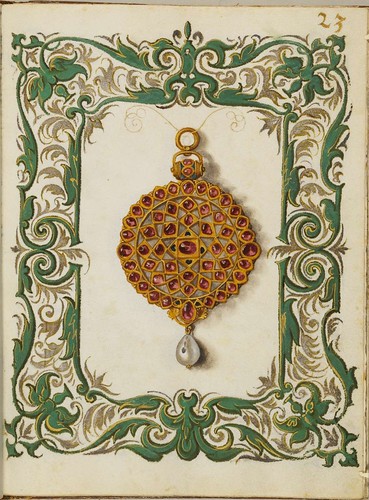

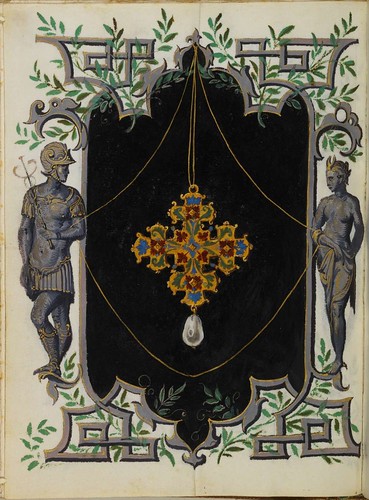

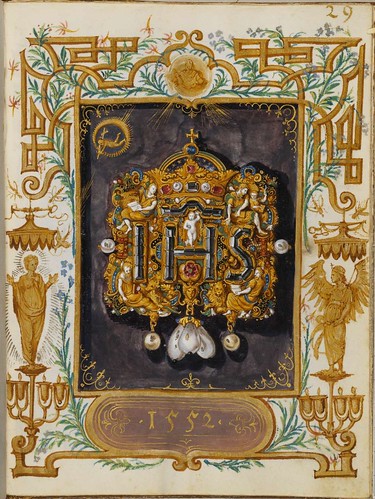

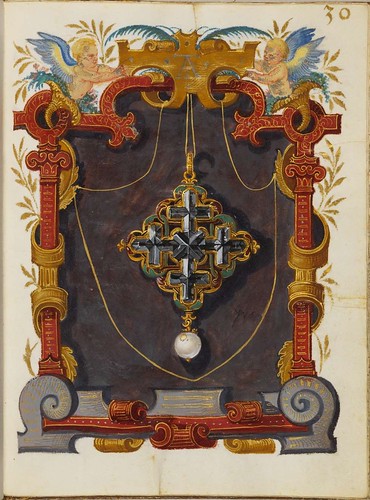

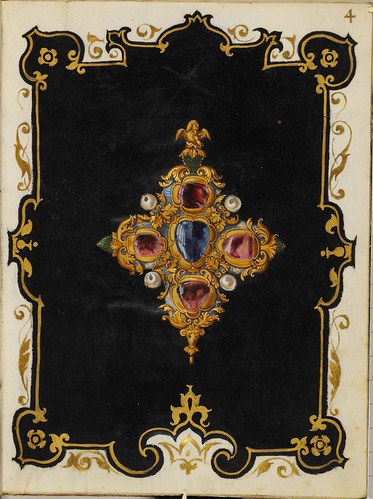

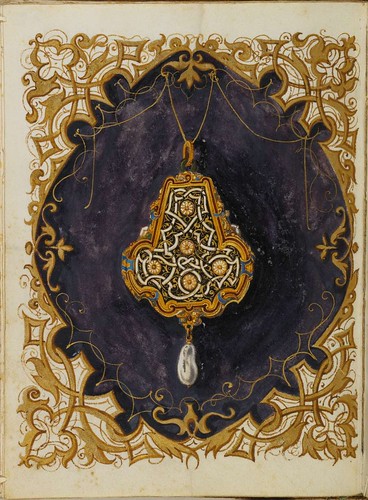

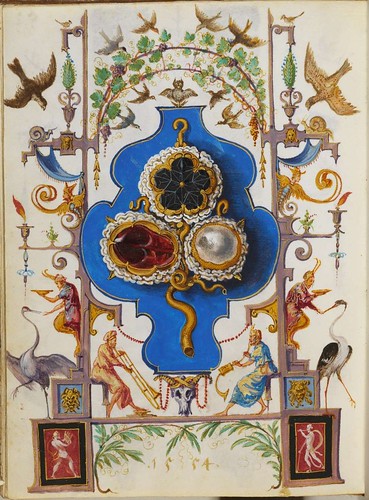

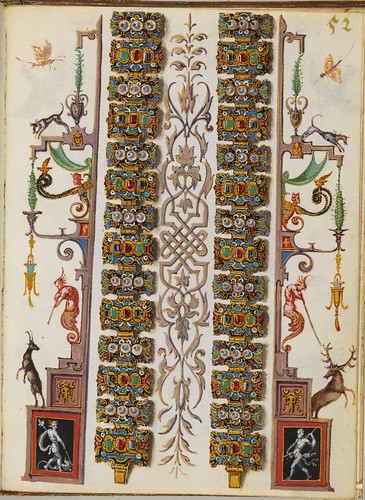

The paper and parchment manuscript displays more than one hundred gouache sketches of seventy pieces of jewellery, the vast majority belonging to Duchess Anna and the remainder to the Duke. Mielich spent at least two years preparing the sketches and the work was completed in 1555.

To be honest, my attention was primarily drawn - at first - not to the jewellery itself, but to the borders and frame decorations. It's essentially a parade of Renaissance and classical motifs featuring strapwork, grotesques, caryatids, arabesques, cartouches, foliage and the occasional animal and trophy. Bearing in mind that the above selection is just a sampling, the manuscript as a whole offers a dizzying array of these decorative forms. The jewels themselves are exquisitely detailed. It may have taken me a while to warm up to it, but this really is a gorgeous manuscript.