In Oddities, A Book of Unexplained Facts Rupert Gould wrote:

“Around Bouvet Island, it is possible to draw a circle of one thousand miles radius (having an area of 3,146,000 square miles, or very nearly that of Europe) which contains no other land whatever. No other point of land on the earth’s surface has this peculiarity.”Indeed, the tiny uninhabited island – a glacier-covered volcanic shield lying at the far southern end of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge – is literally the most remote place on Earth. Perhaps then it’s no wonder that it proved so elusive to 18th and 19th century polar explorers.

Rupert Thomas Gould (16 November 1890 – 5 October 1948), was a lieutenant commander in the British Royal Navy noted for his contributions to horology (the science and study of timekeeping devices). He was also an author and television personality.

Gould grew up in Southsea, near Portsmouth, where his father, William Monk Gould, was a music teacher, organist, and composer. He was educated at Eastman's Royal Naval Academy[1] and then, from 15 January 1906 on, he attended the Royal Naval College, Osborne, and then the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, being part of the 'Greynville' term (group), and by Easter 1907, examinations placed him at the top of his class. He became a midshipman, and thereby a naval officer, on 15 May 1907. He initially served on HMS Formidable and HMS Queen (under Captain David Beatty) in the Mediterranean. Subsequently he was posted to China (first aboard HMS Kinsha and then HMS Bramble). He chose the "navigation" career track and, after qualifying as a navigation officer, served on HMS King George V, and HMS Achates until near the outbreak of World War I, at which time he suffered a nervous breakdown and went on medical leave. During his lengthy recuperation, he was stationed at the Hydrographer's Department at the Admiralty, where he became an expert on various aspects of naval history, cartography, and expeditions of the polar regions. In 1919 he was promoted to Lieutenant-Commander (retired).

On 9 June 1917 he married Muriel Estall. That marriage

ended by judicial separation in November 1927. They had two children, Cecil (born

in 1918) and Jocelyne (born in 1920). His last years were spent at Barford St Martin near

Salisbury, where he used his horological skills to repair and restore the

defunct clock in the church tower.

Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier was

educated in Paris then studied navigation at St. Milo. He joined the

French East India Company and by 1731 had reached the rank of

lieutenant.

At the young age of 30 he petitioned his employers with a plan for an

“exploratory mission” of the southern seas for land that could

accommodate French trading vessels on route to the Far East.

On 19 Jul 1738, outfitted with the Aigle and Marie he

set sail for Brazil. After repairs and provisioning on Santa Catarina

Island he sailed south, crossing the 44th parallel in early December.

By the end of the month the expedition was some 1600 miles from

inhabited land sailing in increasingly difficult, uncharted polar

waters.

At 3:00 pm on New Years Day, 1739 he spotted “a very high land,

covered with snow, which appeared through the mist.”

He spent 12 days attempting to harbor but found that conditions made it

impossible. With his crew nearly freezing to death and suffering from

scurvy he was forced to turn north, eventually

reaching the Cape of Good Hope on Feb 24. Bouvet was convinced that the land he found was a

promontory of the fabled Terra Australis and named it Cap de la

Circoncision (Cape of Circumcision). It was, according to

his

calculations, 54°S, 11°E, making it the southernmost point of land ever

sighted.

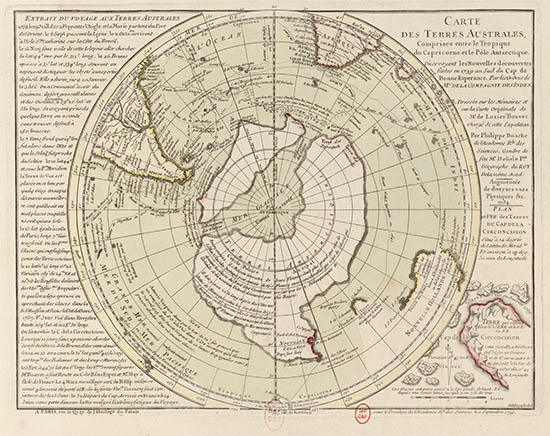

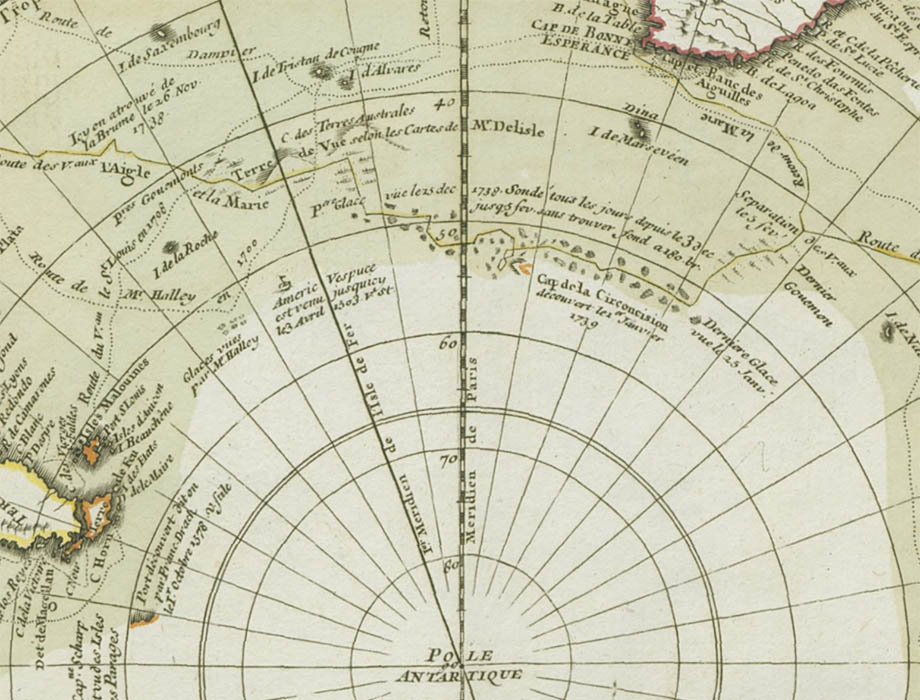

The map of his voyage (above) prepared by Philippe Buache, a

leading polar theorist, became

immediately influential, adding to the scant cartographic knowledge

below the 50th parallel. In 1754 Buache prepared a second edition of the map showing the Cape

of Circumcision attached to his fanciful rendition of Terres

Antartiques:

Carte des Terres Australes, 1754.

BNF

Accurate reckoning of longitude was the fundamental

problem of 18th century navigation and Bouvet’s calculations placed his

discovery considerably too far east. James Cook, on the

Antarctic leg of his 1772 and 1776 expeditions, attempted locate

Bouvet’s Cape with no success.

The Cape was next sighted in 1808 by James Lindsay, captain of the British whaler Snow Swan. He, too, was unable to land, although he did recognize the promotory as an island which he circumnavigated and

named after himself

– Lindsay Island. The first landing occured in 1822 by the American Benjamin Morrell aboard the seal hunting ship Wasp. Morell named it Bouvettes Island, in honor of its discoverer.

Three years later George Norris, master of the British whaler Sprightly, landed on the island, claimed it for the British Crown and named it Liverpool Island.

Then the island simply disappeared. Subsequent explorers, such as

James Clark Ross in 1843 or Thomas Moore in 1845, all failed to again

locate it. As Boudewijn Büch famously wrote

“[they] knew it existed, but that’s all [they] knew."

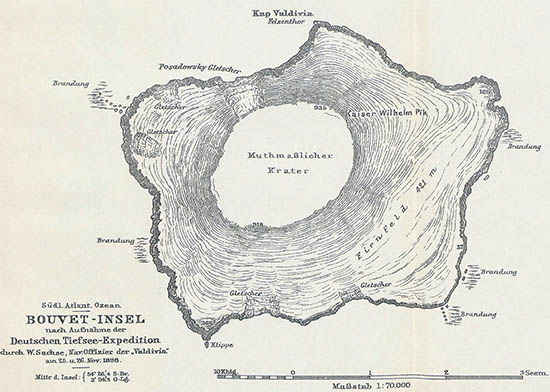

The island was rediscovered by the marine biologist Carl Chun during his 1898 German Deep-Sea Expedition aboard the steamer Valdivia.

On 3 Nov 1898,

at the exact same time of day Bouvet recorded his sighting 159 years

earlier, he spotted the island and made the first accurate calculations

of its size (19 mi2) and position (54°26'4"S. 03°24'2"E).

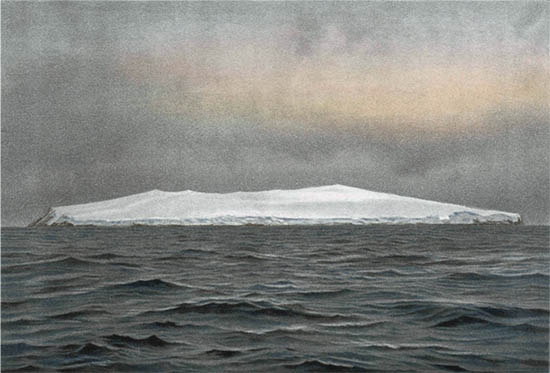

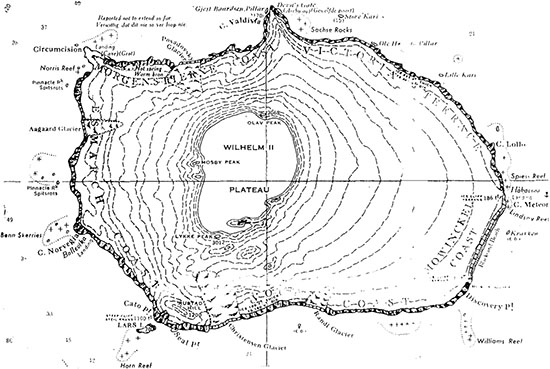

The accounts of the expedition included the first photographs and map:

Bouvet Island, southeast side, as seen at sunrise, eight miles distant, Nov 26, 1898.

Bouvet Island, south side Nov 26, 1898

Bouvet-Insel

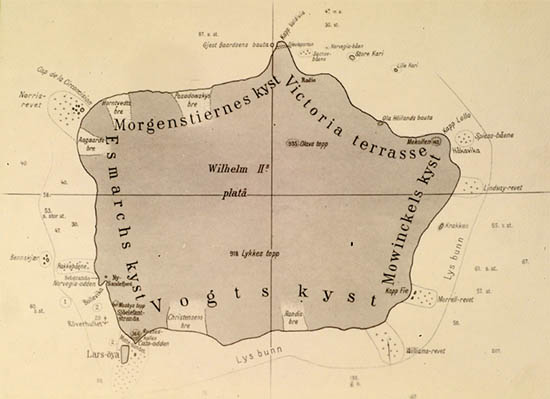

Although remote and inhospitable, Bouvet was still

of interest to 20th century whalers. The Norwegian entrepreneur Lars

Christensen identified the island as a potential site

for a whaling station and in 1927 sent his research vessel Norvegia

to investigate. Although the island, with its nearly vertical cliffs,

was a poor choice for a station, the crew under captain Harald Hornvelt

landed on Bouvet,

built a hut (the Villa Haapløs), and claimed the island for King Haakon

VII. Despite British objections, this claim has stood.

Depot at Cape Circoncision on Bouvet Island, 1927. Norsk Polarhistorie

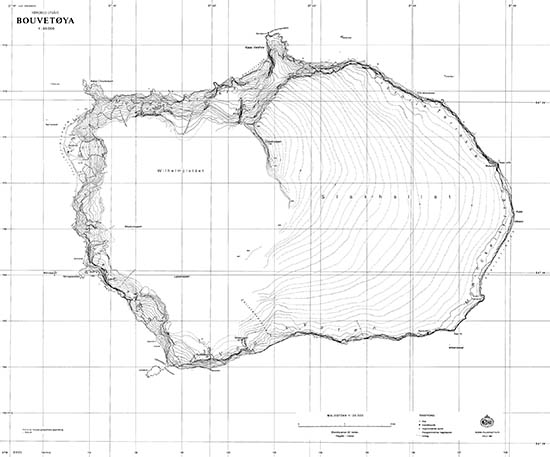

Here is the expedition’s map of the island:

Bouvet-Insel, 1927

Since the Norwegian annexation the island has been

visited sporadically by scientific expeditions. For the International

Geophysical Year and again in the 1960s the Royal South African Navy

conducted meteorological expeditions. They performed the first true

surveys and the RSA Hydrographic Office produced a map in 1955 and a

bathymetric chart in 1967. For two decades these were the best maps of

the island available.

Here is a sadly 2-bit version of the 1955 map:

Bouvet Island, 1955. From ref. 6

The 1977/78 Norwegian Antarctic Research Expedition

performed a completely new survey, including helicopter photogrammetry,

doppler satellite geodesy and echo sounder hydrography. Their maps,

although the most detailed to date, were nevertheless incomplete;

constant low cloud cover prevented mapping of the

eastern slope of the island. In his description of the map Sigurd Helle

wrote “A future, more complete surveying may indeed give a new map which

may deviate from the enclosed.”

Bouvetøya 1:20 000, 1981

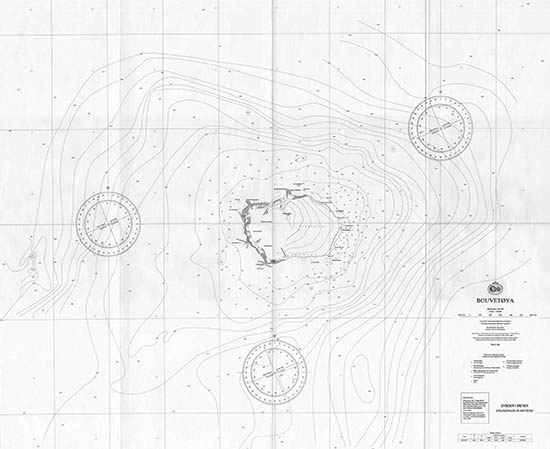

Bouvetøya 1:60 000, 1981.

The 1985/86 Norwegian expedition, blessed with a

unusual period of cloudless weather, was able to photograph the entire

island, establish new control points and complete the

earlier surveys.8 Their new topographical map was published

in 1986 and updated several times. It may very well be the last great

paper map of the island

Bouvetøya 1:20 000, 2000. Norsk Polarinstitutt

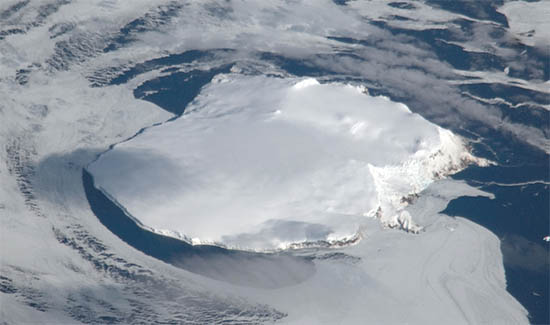

Today, in an era of high-res remote sensing, no place is truly too remote – its all just a satellite photo away:

Bouvet Island from the ISS, 13 Sep 2008. NASA

Bouvet Island from Landsat 8, 26 May 2013. NASA

1. Gold, Rupert. “The Auroras, and Other Doubtful Islands” in Oddities, A Book of Unexplained Facts. London: Philip Allan & Co., 1928

(WorldCat).

2. Bouvet named his newly-discovered cape after the 1 Jan Catholic Feast of the Circumcision.

3. See: Büch, Boudewijn. Eilanden. Amsterdam: De Arbeiderspers, 1991 (WorldCat).

4. Chun, Carl. Aus den Tiefen des Weltmeeres: Schilderungen von der Deutschen Tiefsee-expedition. Berlin: Gustav Fischer, 1903

(online).

5. Die Deutsche Tiefsee-Expedition auf dem Schiff “Valdivia,” 1898/1899: Nach Amtlichen Berichten. Berlin: 1899

(online).

6. Burdecki, Felix. Errichtung einer Wetterstation auf Bouvet Oya? Polarforschung. 1965 35 (1/2): 38–41

(online).

7. Bouvetøya, South Atlantic Ocean: Results from the Norwegian Antarctic Research Expeditions 1976/77 and 1978/79. Skrifter 175. Oslo: Norsk Polarinstitutt, 1981

(online).

8. Report of the Norwegian Antarctic Research Expedition (NARE) 1984/85. Rapportserien 22. Oslo: Norsk Polarinstitutt, 1985

(online).

No comments:

Post a Comment