The Book of Durrow, or the Codex Usserianus I is perhaps the oldest surviving Insular gospel, was written around 650–675 either at the Durrow Abbey, County Offaly, Ireland, or in Northumbria, England. Wherever it was written, however, it ended up at the Durrow Abbey, where a cumdach (a silver covering) was made to house the manuscript. An inscription added to the text stated: “the prayer and benediction of St. Columb Kille be upon Flann, the son of Malachi, King of Ireland, who caused this cover to be made.”

The manuscript apparently remained at Durrow until the abbey was dissolved in the mid-16th century. According to legend the next custodian of the manuscript placed it in his watering trough to cure his cattle of sickness. Later, sometime around 1662, Henry Jones, Bishop of Clogher and Vice-Chancellor of Trinity College, presented the book to the college library, where it remains to this day.

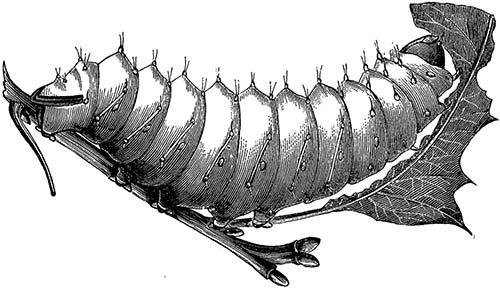

Folio 22, recto

By the time Christianity was introduced into Ireland by St. Patrick, nomadic Germanic tribes, such as the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians had conquered much of Europe, including England. Ireland, however, was apparently not all that important to the marauding Germanic pagans and they were left alone to develop a unique version of monastic Christianity. So when St Columbia reintroduced Christianity back into England by establishing monasteries in Iona, Scotland in 563 and Northumbria in 635 these Germanic and Celtic artistic traditions merged – a cross-pollination of sorts – into what is now known as Insular or Hibero-Saxon art.

The Insular scribes and illuminators were heavily influenced by Hibero-Saxon crafts: The complex interlaced knotting, perhaps the most recognizable Insular form, was borrowed from Celtic metalwork, the iconography of animals was borrowed from Germanic zoomorphic designs and the images of the Jesus and the Evangelists from Pictish grave markers. Of course, of all these other sources are now largely forgotten and it is the manuscripts that define the art.

The Insular manuscript ended with the invasion of Ireland by the Normans in 1169–1170, which ushered in the Romanesque style. Many insular design elements, however, continued to be adapted and used as decorative motifs. A millenium later Insular design, often under the misnomer Celtic design, continues to be popular

The Book of Durrow contains the complete compliment of Insular designs. Each gospel is laid out with a full-page miniature of the evangelist or his symbol:

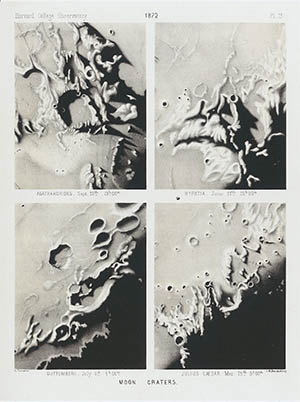

Portrait of Mark. Folio 84, verso

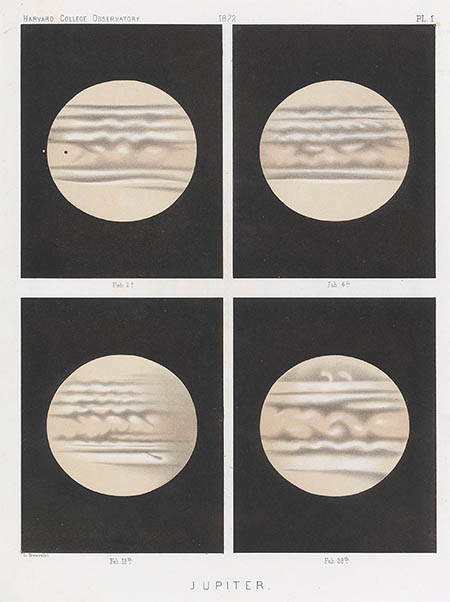

Then a purely ornamental full-page geometric design – a carpet page, named after its resemblance to a Persian rug:

Carpet page. Folio 85, verso

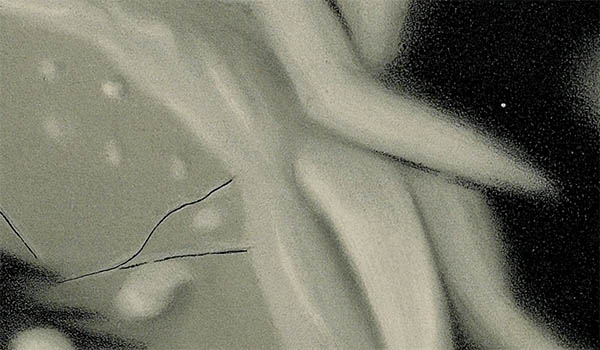

Then an incipit page where the text begins with an elaborately decorated initial letter. These historiated initials became so large that they were integrated into the rest of the text by several lines of decreasing size – an effect known as diminuendo:

Incipit of Mark. Folio 86, recto