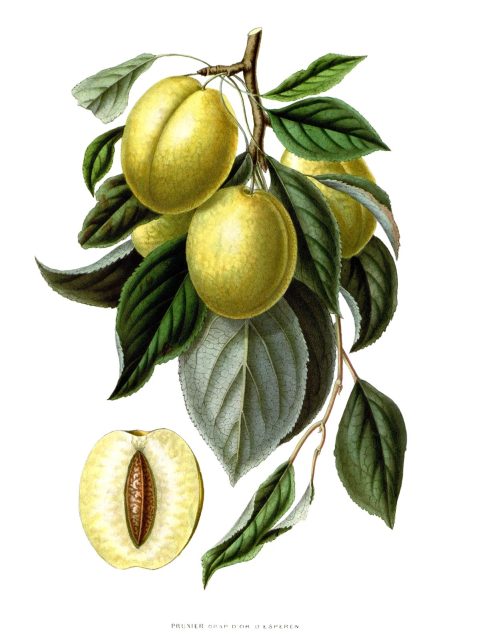

Golden Esperen plum.

From Flore des Serres et des Jardins de l’Europe (Flowers of the Greenhouses and Gardens of Europe) vol. 4, by Charles Lemaire, Michael Scheidweiler, and Louis van Houtte, Ghent, 1848.

From Flore des Serres et des Jardins de l’Europe (Flowers of the Greenhouses and Gardens of Europe) vol. 4, by Charles Lemaire, Michael Scheidweiler, and Louis van Houtte, Ghent, 1848.

Flore des Serres et des Jardins de l'Europe ('Flowers of the Greenhouses and Gardens of Europe') was one of the finest horticulture journals produced in Europe during the 19th century, spanning 23 volumes and over 2000 coloured plates with French, German and English text. Founded by Louis van Houtte and edited together with Charles Antoine Lemaire and Michael Joseph François Scheidweiler, it was a showcase for lavish hand-finished engravings and lithographs depicting and describing botanical curiosities and treasures from around the world.

The work is remarkable for the level of colour-printing craftmanship displayed by the Belgian lithographers Severeyns, Stroobant, and De Pannemaker. Louis-Constantin Stroobant (1814-1872), printed many of the illustrations for the first 10 volumes. Most of the plants depicted in Flore des Serres were available for sale in van Houtte's nursery, so that in a sense the journal doubled as a catalogue.

The editors were experienced botanical engravers and horticulturists, combining their knowledge and skills to create a showpiece of novel exotics and familiar cultivated plants. Lemaire came from being an engraver for Redoute's great works Les Liliaces and Les Roses. van Houtte, owner of the most successful nursery on the Continent at that time, sent his own plant explorers to find unknown orchids and other exotics, and to return them to Ghent for cultivation at his nursery, and later publication in Flore des Serres.

The work is remarkable for the level of colour-printing craftmanship displayed by the Belgian lithographers Severeyns, Stroobant, and De Pannemaker. Louis-Constantin Stroobant (1814-1872), printed many of the illustrations for the first 10 volumes. Most of the plants depicted in Flore des Serres were available for sale in van Houtte's nursery, so that in a sense the journal doubled as a catalogue.

The editors were experienced botanical engravers and horticulturists, combining their knowledge and skills to create a showpiece of novel exotics and familiar cultivated plants. Lemaire came from being an engraver for Redoute's great works Les Liliaces and Les Roses. van Houtte, owner of the most successful nursery on the Continent at that time, sent his own plant explorers to find unknown orchids and other exotics, and to return them to Ghent for cultivation at his nursery, and later publication in Flore des Serres.

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea, syn. Echinacea intermedia)