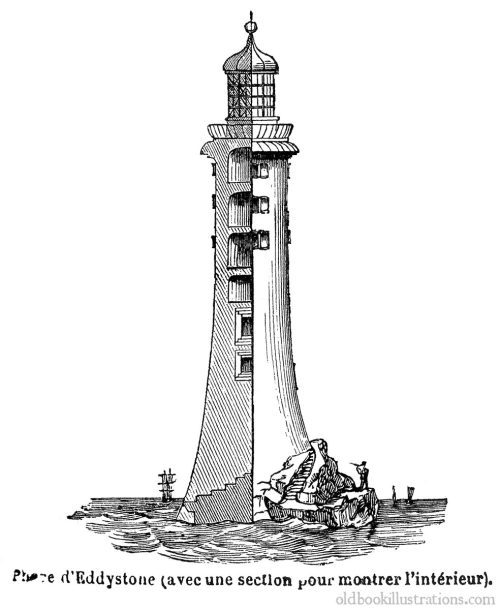

(And while I’m at it, another view of Eddystone.)

From the Trousset encyclopedia, Paris, 1886 - 1891.

(Source: Old Book Illustrations)

From the Trousset encyclopedia, Paris, 1886 - 1891.

(Source: Old Book Illustrations)

A floating beacon or buoy.

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

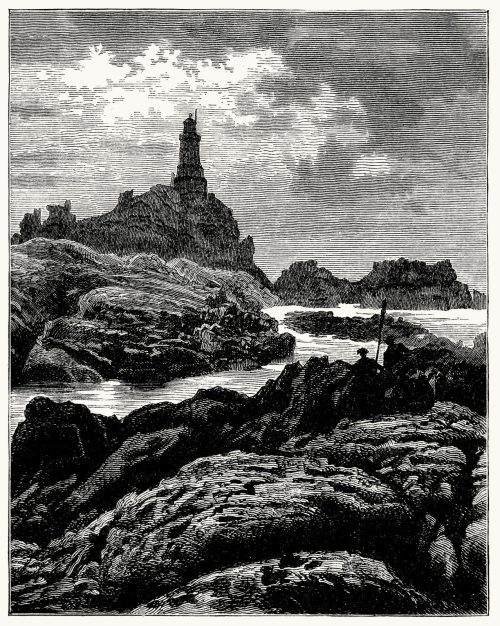

The Corbières lighthouse.

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

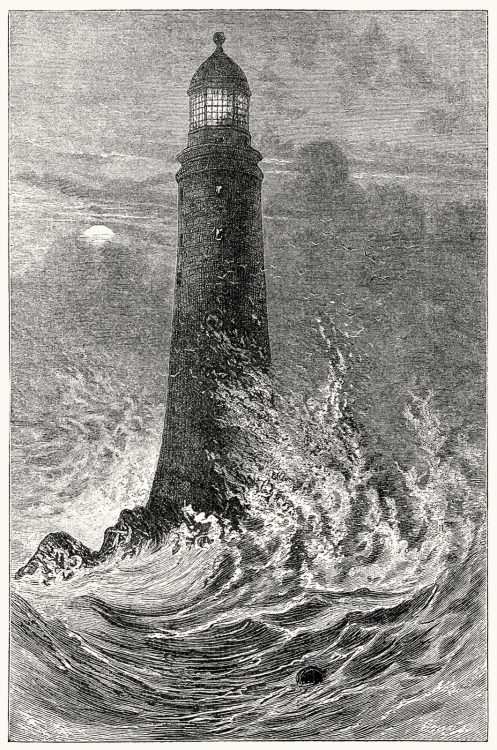

Smeaton’s lighthouse at the Eddystone.

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

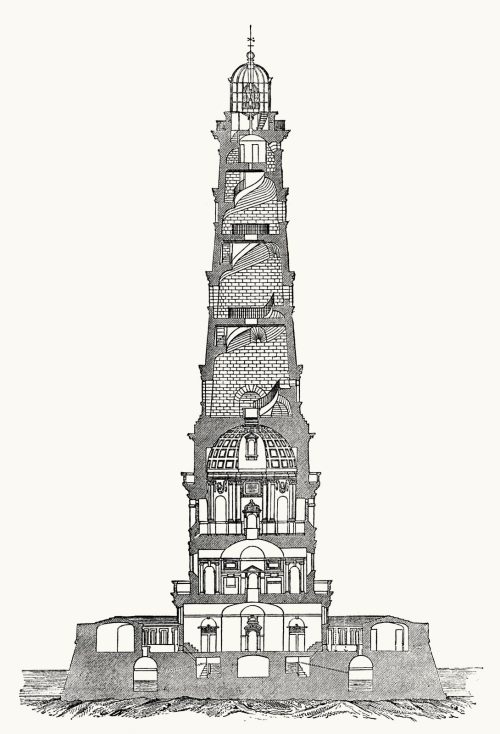

Interior of the Corduan lighthouse.

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

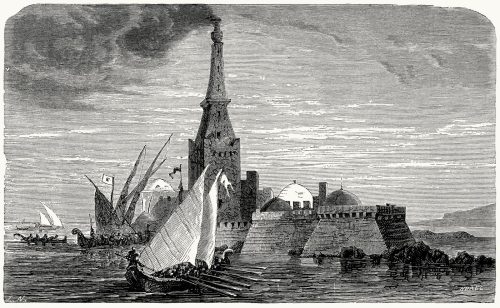

Ancient pharos of Alexandria.

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

From The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

Front cover from The story of our lighthouses and lightships, by W. H. Davenport Adams, London, 1891.

(Source: archive.org)

(Source: archive.org)