After the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) there

was a growing desire by the laity to more closely imitate the devotions

of the monastic monks and nuns, but the psalter or the breviary

were entirely too complex and variable. What was needed was a “Breviary for Dummies” and this would be the The Book of Hours.

A Book of Hours was intended as a small, and personal, book of devotion.

Although the contents varied to some extent, generally it began

with a liturgical calendar followed by extracts from the four gospels,

the Hours of the Virgin, the Hours of the Cross and the Hours of the Holy Spirit.

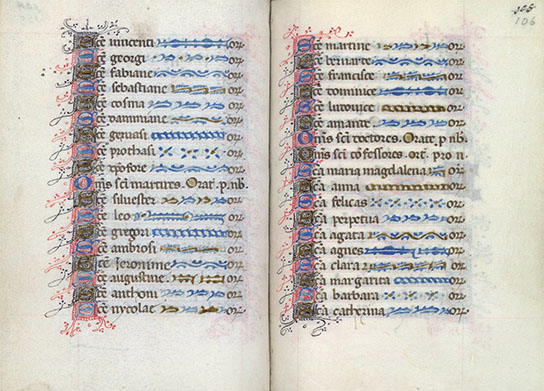

The book concluded with the Office for the Dead,

the Seven Penitential Psalms, the Litanies, and prayers to the Virgin and other saints.

Although less expensive than, e.g., a Bible, a Book of Hours was still within reach of only the wealthy.

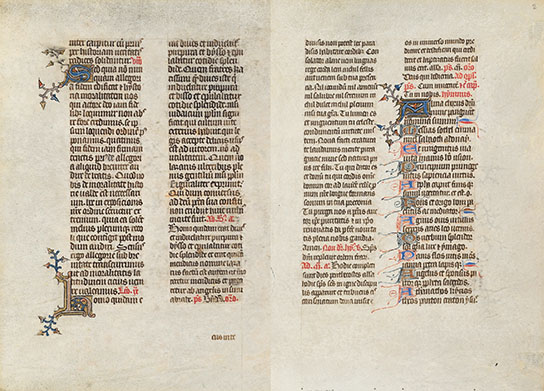

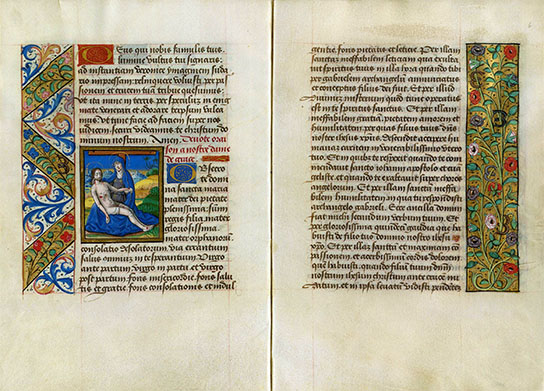

Early examples from the 14th century are comparatively plain, but the amount of work and expense that

went into their creation is still rather apparent:

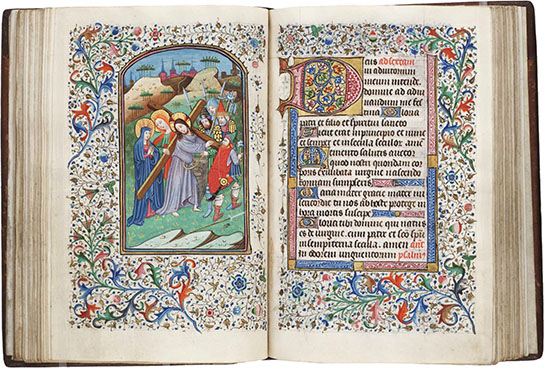

The popularity of the Book of Hours reached its peak by the middle of the 15th century.

Nobility and the wealthy were commissioning increasingly deluxe versions of the manuscript; versions

that required not only a scribe (or several) but also illuminators and artists for the

extravagant miniatures (often including the family’s coat-of-arms), illumination and decoration.

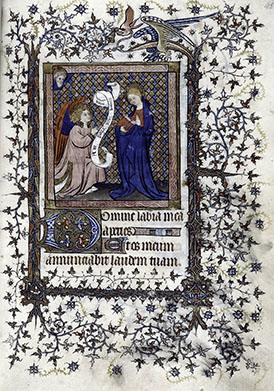

The Annunciation, f. 23r. France, ca.1400. NYPL

Gethsemene, f. 14r. Flanders, ca.1485. UT Austin

Jesus on the Mount of Olives, f. 1r. France, ca.1475. Columbia

The Book of Hours was produced throughout Western Europe, but it was especially popular in France

and the Low countries. By 1430 stationers in Paris and Ghent

(among others) began to mass-produce the books,

sometimes using tipped-in plates, for “middling merchants and local

gentry, people with social pretensions who would be attracted by

something which looked more expensive than it really was.”

The Book of Hours was by far the most commonly produced book of the

late middle ages. Even after the advent of mechanical type it was still

commissioned as a luxury item for the

wealthy and powerful, but by the middle of the 16th century it had been

mostly replaced by a simpler, and much

less costly devotion – praying the rosary.

The Legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead, f. 113r. Bourges, ca.1500.

Philadelphia

- Most, but not all, of these images are from the holding institution via Columbia University’s spectacularly wonderful -I do recommend the visit- Digital Scriptorium.

- For more information on the Book of Hours, including a

complete translation of a later English Primer version, see the

appropriately named Hypertext Book of Hours.