Étienne Léopold Trouvelot was born on 26 Dec 1827 in Guyencourt,

France.

As a young man he dabbled in politics, becoming a staunch Republican.

After Louis Napoleon’s coup in 1852 he fled to America with

with his wife Adelaide and settled in Medford, just outside of Boston.

He listed his occupation as lithographer.

Although an artist Trouvelot had a keen interest in science and

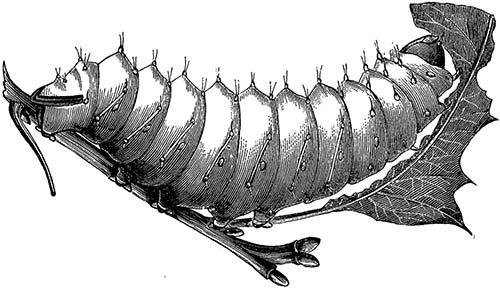

turned his attentions toward sericulture. Hoping to become rich in the

American silk trade

he raised giant silk moths (Antheraea polyphemus), eventually having as many as a million larvae under nets on his five acre property in what he called his “infant industry.”

Trouvelot, the American Silk Worm, 1867

In Mar 1867 he returned from France with live gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar)

eggs, intending to cross the two moths to develop a disease resistant

strain. It would turn out to be a bad idea;

not only are gypsy moths and giant silk moths two entirely different

species but

sometime around 1868-69 some of the moths escaped his nets. He had –

quite inadvertantly – introduced the gypsy moth to North America. He

knew enough at the time to become alarmed, but after contacting other

entomologists there was apparently little concern.

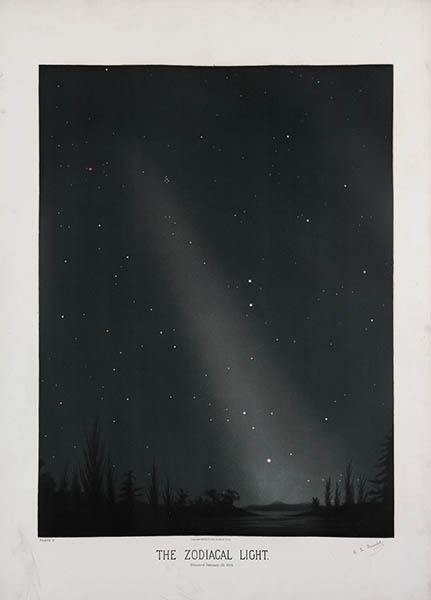

The gypsy moth incident was the beginning of the end

of his interest in entomology. In 1870, after observing the aurora, he

embarked on his next scientific obsession – astromony.

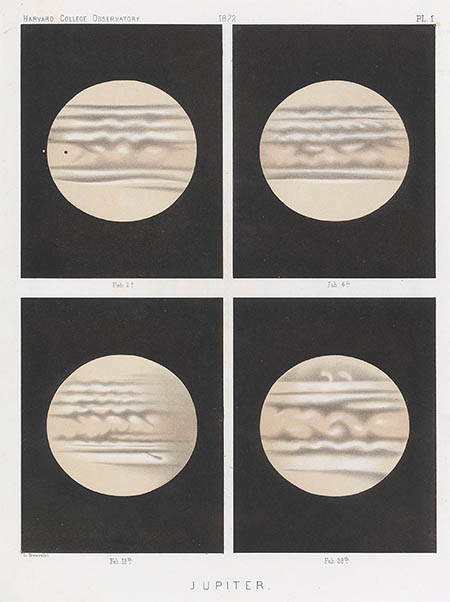

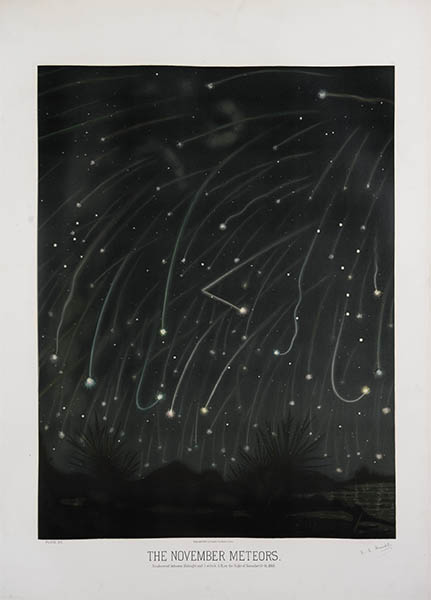

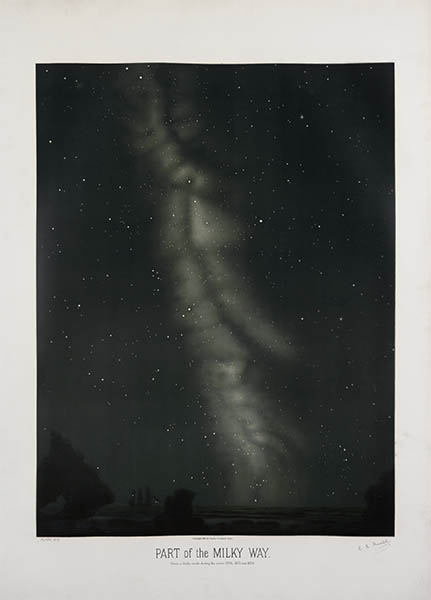

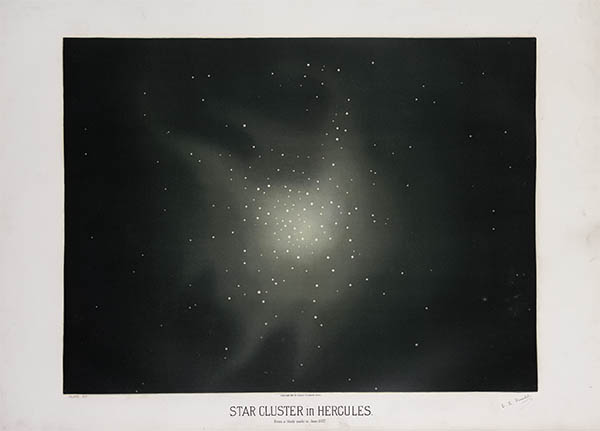

He bought a 6-inch telescope and began preparing drawings that caught

the attention of Joseph Winlock who invited him to use the 15-inch Great

Refractor at the Harvard College Observatory.

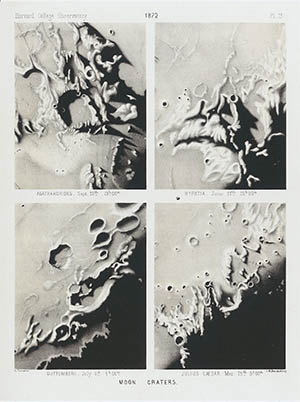

His work under the especially clear skies at Cambridge set a new

standard for astronomical illustration that wouldn’t be surpassed until

the perfection of the photographic dry-plate. In 1872 The New York Times

wrote

“a person entirely ignorant of astronomy could not fail to be much

impressed with [Trouvelot’s] drawings.” Here are a few examples from

the 1876 Harvard Annals

Harvard University Library

In 1875 Trouvelot was invited to the US Naval

Observatory to continue his work using the 26-in Great Equatorial, then

the largest telescope in the world.

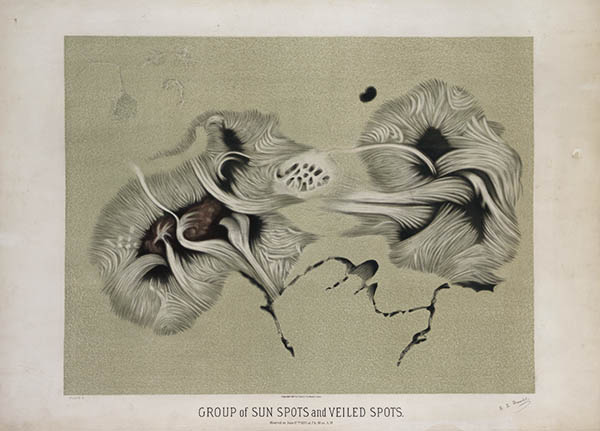

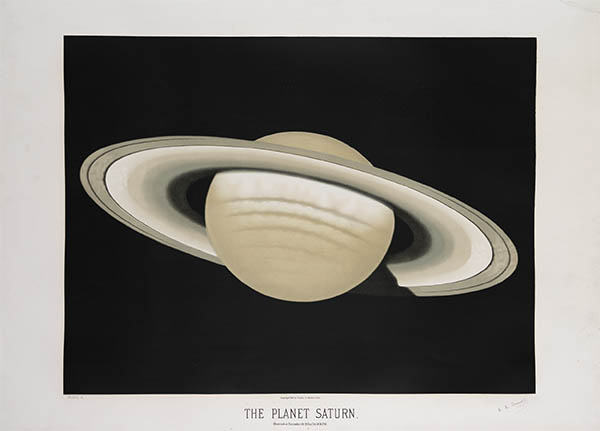

As part of the observatory’s exhibit at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition

in Philadelphia he prepared a series of large-format pastel

illustrations:

In the late 1870s Trouvelot approached Scribners,

who had recent experiance with color lithography, to publish some of his

illustrations.

He personally supervised the conversion of his pastels into lithographic

stones

by Armstrong and Co. of Boston. A folio of 15 large-format (24 × 38")

chromolithographs and 167-page descriptive manual was published in 1882

as The Trouvelot Astronomical Drawings.5 Despite its

small edition size (~300) and its rather prohibitive price of 125 USD,

Scribners listed it as one of their most successful titles of the

period.

Here is a detail showing the chromolithographic process:

And here are the rest of the plates:

In 1882 Trouvelot

accepted a position at the Meudon Observatory in Paris. He continued his

astronomical research using their Grande Lunette and even travelled to

the Caroline Islands to observe the total eclipse of 1883.

He wrote that one day he hoped to return to America but he never did. He

died in Meudon on 22 Apr 1895.

Trouvelot was a classic case of the Victorian

autodidact. With no formal training he left behind a legacy of several

books and monographs, more than 50 scientific papers and

nearly 7000 illustrations covering the entire range of natural science –

everything from astromony to moths and butterflies to reptiles to

geological surveys. Of course he will be remembered for his other legacy –

the gypsy moth – which continues to spread across North America and causes nearly a billion USD of damage each year.

1. Unless otherwise noted, all of the images here are from the Public Library of Cincinnati

2. For more bibliography see: Spear, Robert. The Great Gypsy Moth War: The History of the First Campaign in Massachusetts. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005

(WorldCat) or

Corbin, B.G. Etienne Leopold Trouvelot (1827–1895), the Artist and Astronomer. Library and Information Services in Astronomy V, ASP Conference Series.

2007 377: 352– 360 (online).

3. See: Trouvelot, L. The American Silk Worm. American Naturalist 1867; 1(1) 30-38

(online).

4. Bond, W. C., Bond, G. P., Winlock, J. Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College. Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, 1876

(online).

5. Trouvelot, E. L. The Trouvelot Astronomical Drawings. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1882 (WorldCat).

6. Adjusted for inflation that’s more than 3000 USD today. However, according to the Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Scribners

was remaindering copies for only 10 USD in 1886.